Pardon the superlative, but one of the most overlooked movies of the past ten years has to be Wonder Boys, a film directed by Curtis Hanson that follows Grady Tripp (Michael Douglas), an English Professor who deals with a crumbling marriage of his own undoing, a long-term affair that has been impregnated with, well, pregnancy, the visit of Terry Crabtree (Robert Downey Jr.), his book editor who is long-waiting for Tripp’s next novel, one that he’s spent the last seven years penning, unable to make a choice or stop the flow of his pen.

Based on Michael Chabon’s novel of the same name, Wonder Boys is not about “finding one’s self” or “dealing with calamities,” though they happen rather comically throughout the film. Instead, Wonder Boys looks at both the often self-destructive desire to make the temporal infinite as well as the dangers of complacency.

A primary example is Tripp, the author of Arsonist’s Daughter, a novel that seemingly influenced most of the students in his creative writing to attend the university where he works based on his presence. Our character’s accomplishment is notable, and it ultimately provides him with job security though tenure, but it also creates an apex from which Tripp has fallen in his private life and is far from reaching in his present station. This inability to recreate the success of Arsonist’s Daughter doesn’t stem from lack of sales or recognition for his subsequent novels; rather, his inability stems from his failure to finish his second novel, an unnamed, peripatetic tome that exemplifies the antithesis of “writer’s block,” offering instead “textual dysentery,” seemingly never ending and painful for the author each time he types page numbers that reach beyond two thousand.

And within Tripp’s dysentery, the fears of anyone who has reached their apex too early are exhibited, wary that futures attempts won’t resemble their previous accomplishment, miring them in the past. This is further evident by Tripp’s insistence of using an antiquated manual typewriter, replete with ink-covered ribbon. While this could be a sign of superstition, it also mirrors a desire to remain in the past. If he merely meant to relive it, he would transition in to and from contemporary clothing and automobiles. Instead, Tripp exists, shrouded in a raggedy pink bathrobe and tattered clothing, driving a beat up Oldsmobile from the nineteen 70’s.

At the same time, Wonder Boys isn’t totally mocking a desire to remain in the past so much as it’s examining how easily such a time warp can be enabled. In other words, if there’s no impetus to transition, then why do so?

Take for example Tripp’s position as a tenured English Professor. While this information is delivered in a tongue-in-cheek moment when Tripp takes the blame for killing the Chancellor’s dog as opposed to letting James Leer (Tobey Maguire) take the rap because Grady “has tenure,” there’s some poignancy elicited here inasmuch as Arsonist’s Daughter has provided job security that can’t be revoked. Granted, it helps that Tripp is also sleeping with the Chancellor’s wife, Dean Sara Gaskell (Frances McDormand), but the implication here is that Grady has little need to change his pot-smoking, pill popping, wanderlusting lifestyle because of the security afforded to him by a cherished moment of recognized success in the past.

A similar look at remaining in the past can be seen through Grady’s various ex-wives who are alluded to, and although the film begins with the news that Tripp’s wife left him that day, she is never seen. Why? Because she was only a shill for the beautiful, young, adoring wife who was present when Grady penned his first novel. Eventually, the intrigue within the relationship deteriorated, but Grady will soon be off “to find another one,” as Crabtree reminds him: “you always do,” a discourse that exposes the exchangeable nature of the tangible in order to configure one’s self to a comfortable environment, even if that environment existed seven years ago.

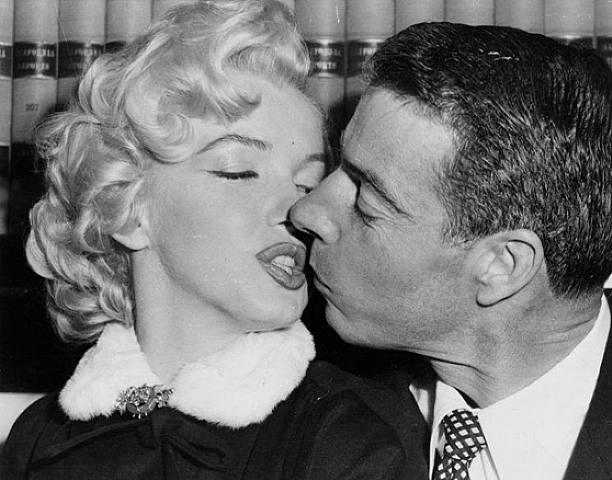

As Grady the person declines, his reputation as a writer continues to precede him, keeping his public image intact, which also extrapolates on the microcosm that is Tripp’s universe and parallels it with a celebrity-obsessed public who perpetuate the visages of deceased celebrities through selective memory, specifically in this movie, Marilyn Monroe and Joe DiMaggio — the players in the “last American marriage” as Chancellor Walter Gaskell (Richard Thomas) asserts. The significance here is that Gaskell’s scholastic research of the famous couple has diverted his wife carries on a long-term affair with Grady.

Much like Grady exchanges wives and typewriter ribbons to fashion a comfortable existence, Gaskell uses memorabilia of the famous couple: DiMaggio’s Yankees jersey and the black with white-fur-trimmed jacket that Monroe wore on their wedding day. These two items of clothing hang next to each other as an undisturbed husband and wife tandem, forever cloistered away in a combination locked, closet-sized safe that would be more aptly called Gaskell’s hope chest, preserving the lives and memories of both celebrities while obviating their respective scandals and transgressions.

Simultaneously, Gaskell’s assertion that Monroe and DiMaggio are “the last American marriage” also exposes his potential knowledge that things are amiss under his roof, but why crumble a fortress of cards that houses a Chancellor and a Dean of the same university?

In the end, it seems that Wonder Boys’ greatest feat is exploring public perception versus the knowledge of our own reality that can be so easily tossed about in the wind like a lime green ’79 Pinto.